Het Maakonderwijs

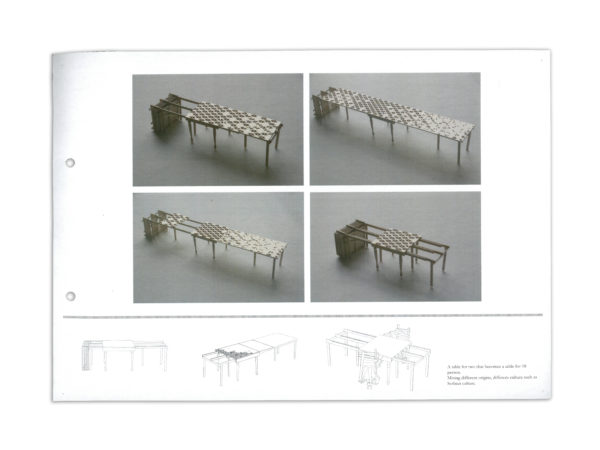

In zijn standaardwerk ‘The Craftsman’ omschrijft Richard Sennett het ambachtschap in het kort als “de bedrevenheid (de kunde) om dingen goed te doen.” Hij gaat verder: “Ambachtschap benoemt een doorlopende, basale menselijke impuls, het verlangen om een beroep goed uit te voeren ‘for its own sake’.” Bedrevenheid, toewijding en inschattingsvermogen zijn drie belangrijke dimensies die een professional een ambachtsman maken volgens Sennett. Ambacht betreft niet alleen analoge beroepen (technieken in de houtbewerking), maar alle beroepen. Zelfs nieuwe technische beroepen – die meestal niet worden geschaard onder de ambachten – worden door een continue nieuwsgierigheid en toewijding van de uitvoerder een ambacht. Zouden we dit betrekken op het MBO-onderwijs, dringt zich de vraag op hoe ambacht een plek vindt in de huidige MBO opleidingen.

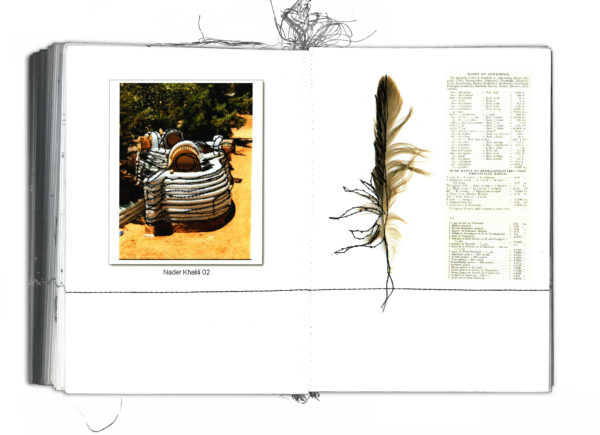

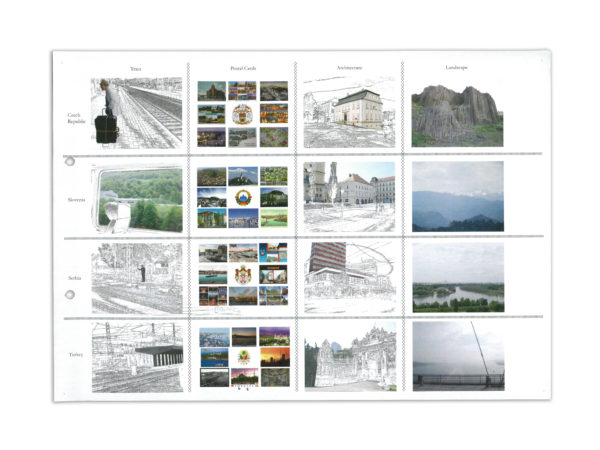

Nieuwe technologieën, technieken en materialen vragen om een nieuwe aanpak van educatie, door alle niveaus van onderwijs heen. Voor educatie voor de maakindustrie is het wellicht het meest urgent om methodes en structuren te herzien. Binnen de lijst beroepen waartoe mbo-colleges opleiden zijn een aantal beroepen al verhuisd naar lage-lonen landen en anderen door verdere automatisering en robotisering binnen een aantal jaar obsoleet zullen zijn, zoals administratief medewerker en boekhouder. Het ligt in de lijn der verwachting dat de banen in de nijverheden sector zullen afnemen door technologische ontwikkelingen. Maar er ontstaan ook nieuwe beroepen en ambachten door nieuwe ontwikkelingen in de industrie. Die technieken en materialen vergen nog extra onderzoek, een gedegen testfase en er moet nog een toepassing en afzetmarkt worden gevonden. Mbo-colleges zouden daar een belangrijke rol in moeten spelen.

Educatie wanneer kennis alomtegenwoordig is

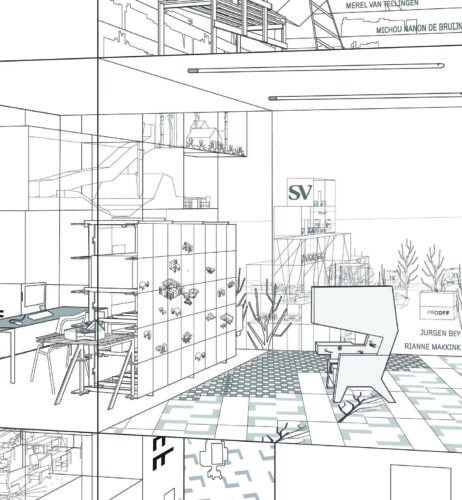

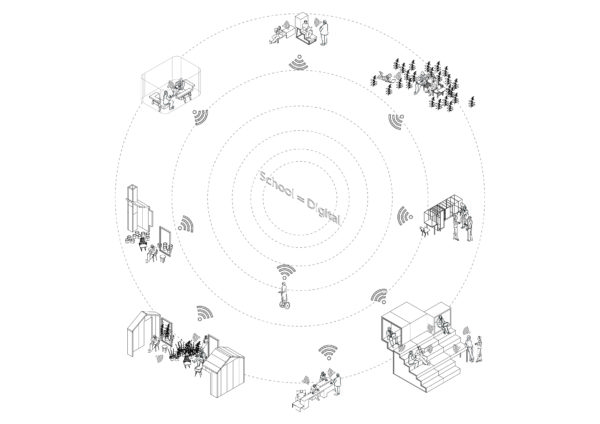

Het internet biedt met de brede beschikbaarheid van kennis ook veel mogelijkheden. Nieuwe technologie is op hetzelfde moment voor docenten als studenten beschikbaar. Op dit gebied hebben studenten dus een enorme voorsprong op hun opleiding en docenten: de docent heeft weinig tijd om nieuwe technieken en materialen te onderzoeken, maar studenten kunnen al hun vrije uren besteden aan het verkennen van een nieuw onderwerp. Binnen de kortste keren lopen zij voor in kennis op de docent. Hiermee verandert de verhouding docent/ student fundamenteel: een docent krijgt een begeleidende rol in het leerproces van de student. Dit betekent niet dat zij overbodig zijn, zij blijven van vitaal belang om langlopende kennis in te brengen, gerelateerde onderwerpen aan te halen en studenten te sturen in hun studie.

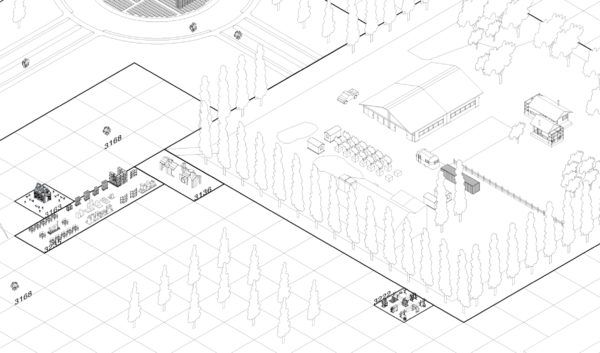

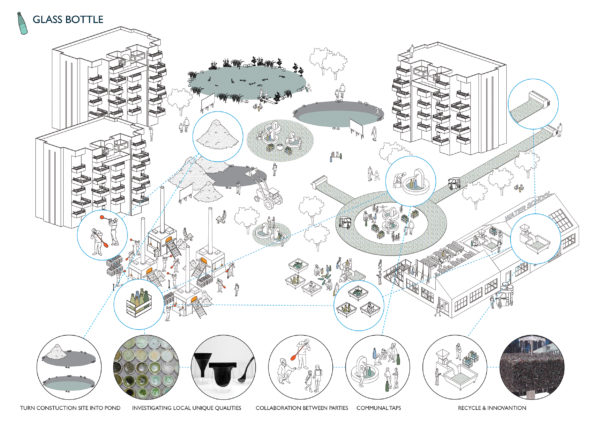

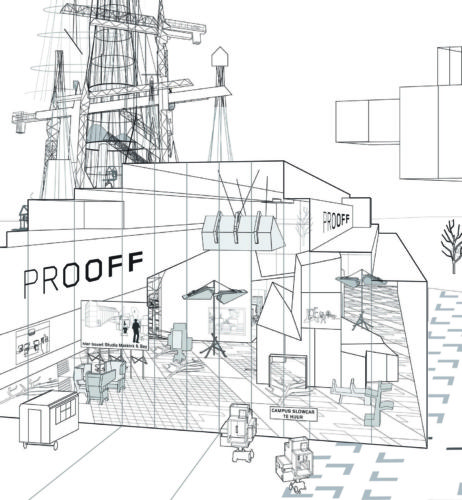

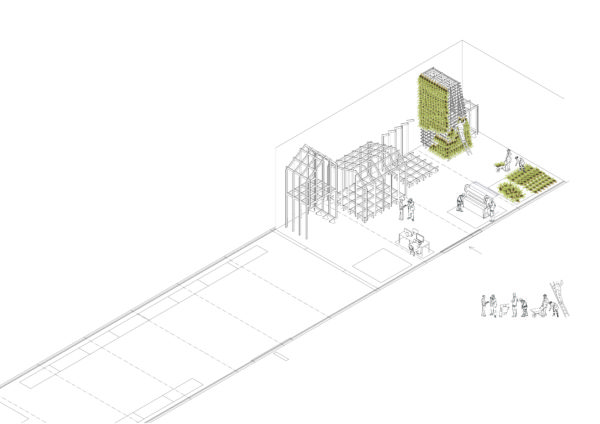

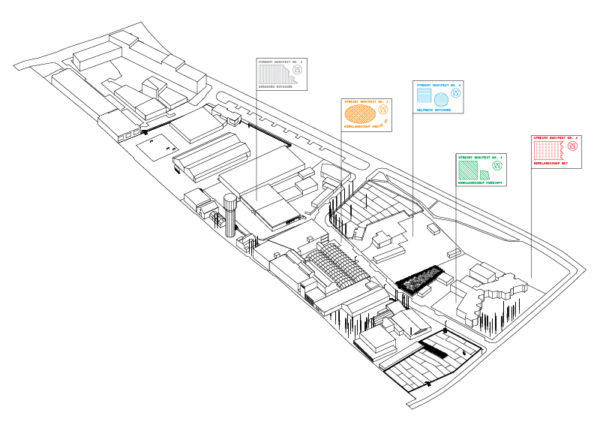

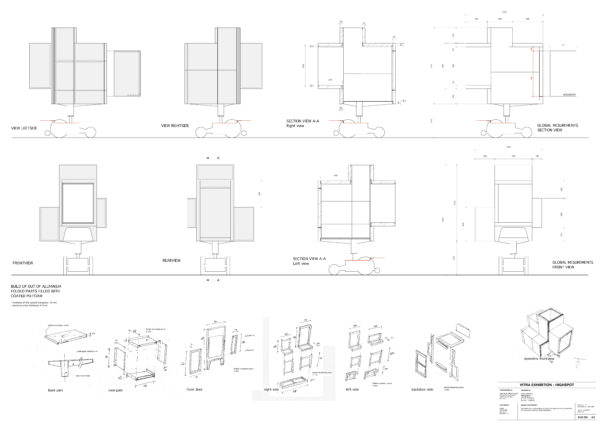

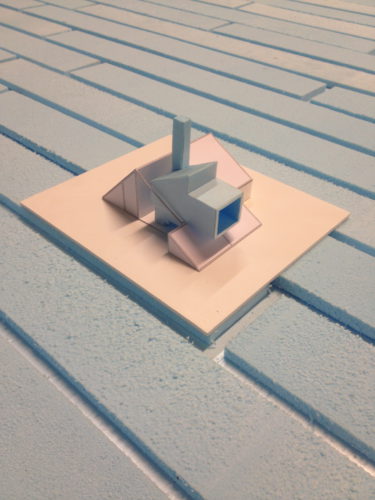

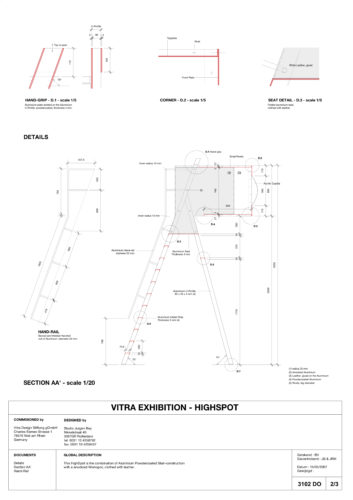

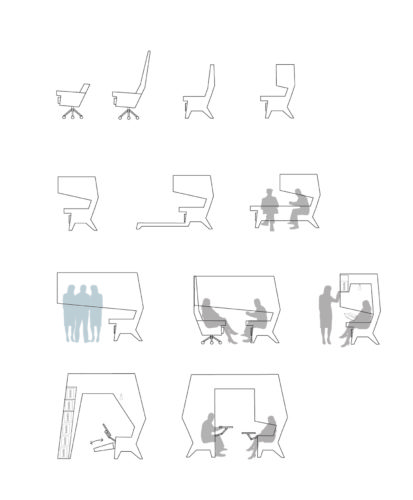

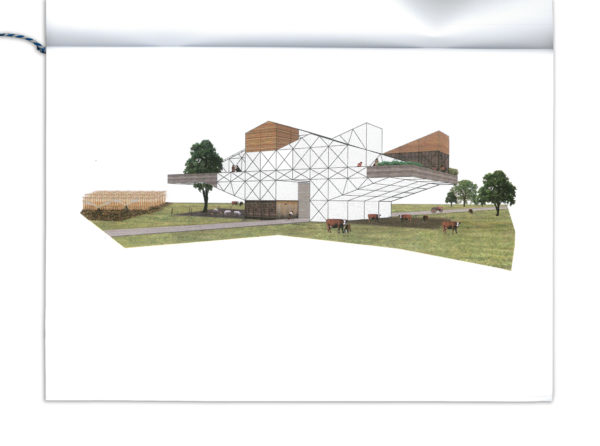

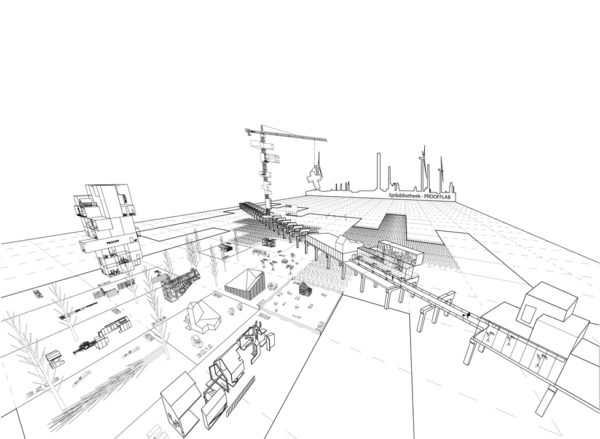

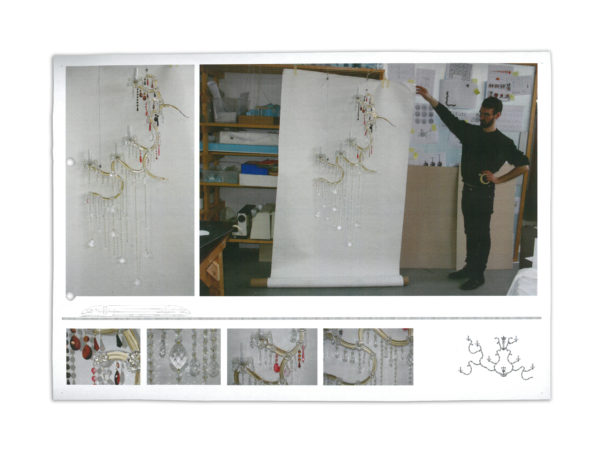

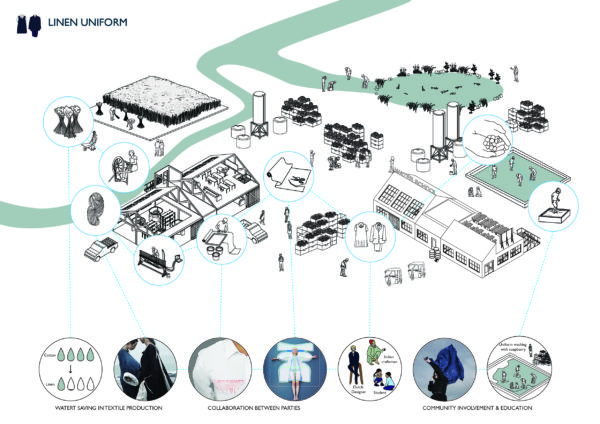

Met nieuwe materialen komen ook nieuwe modellen, waarbinnen mensen zich op een andere manier tot elkaar verhouden. Een gebouw neerzetten waarbinnen een of meerdere functies huizen, is niet langer meer houdbaar – er moeten condities worden geschept om die nieuwe methodes en functies binnen te ontwikkelen, waar experts op andere manieren met elkaar kunnen samenwerken. Deze verandering in betreft uiteindelijk ook het maak-onderwijs waar op dezelfde manier wordt gevraagd naar multidisciplinaire samenwerkingen, flexibele structuren en project gestuurd onderwijs.

De ZeewierSchool

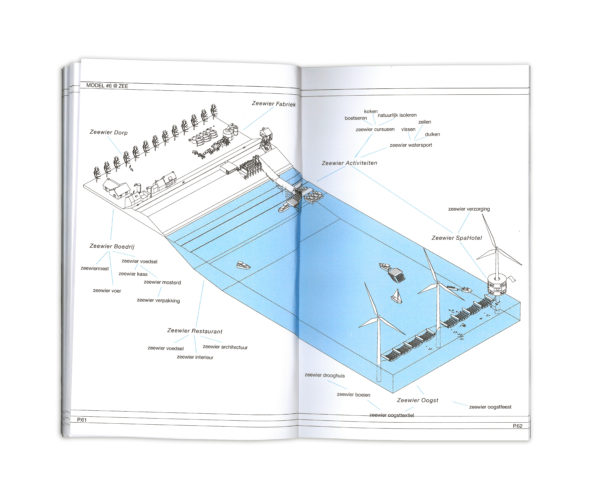

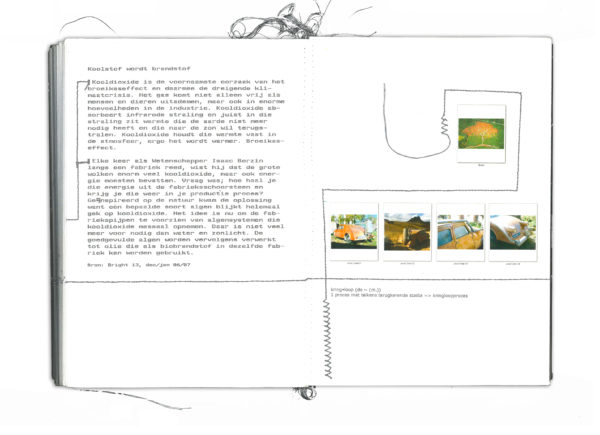

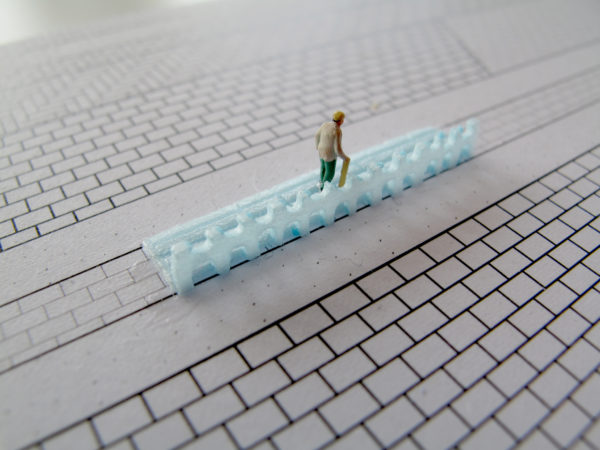

Als een materiaal of een specifieke innovatie de belofte van de toekomst is, hoe kan een opleiding zich daartoe verhouden en haar studenten effectief voorbereiden op hun beroepspraktijk? We werken deze gedachtegang uit aan de hand van zeewier, een grondstof die een dergelijke potentie heeft.

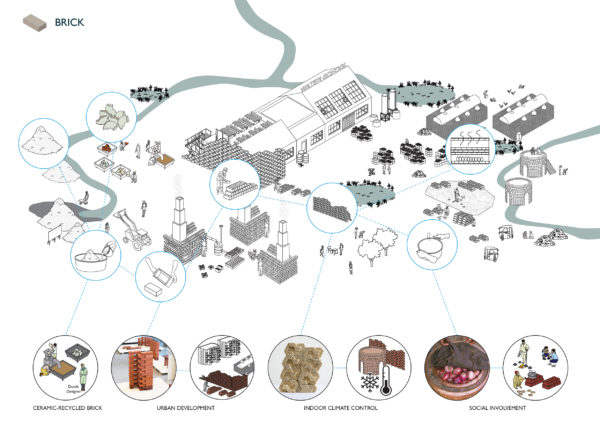

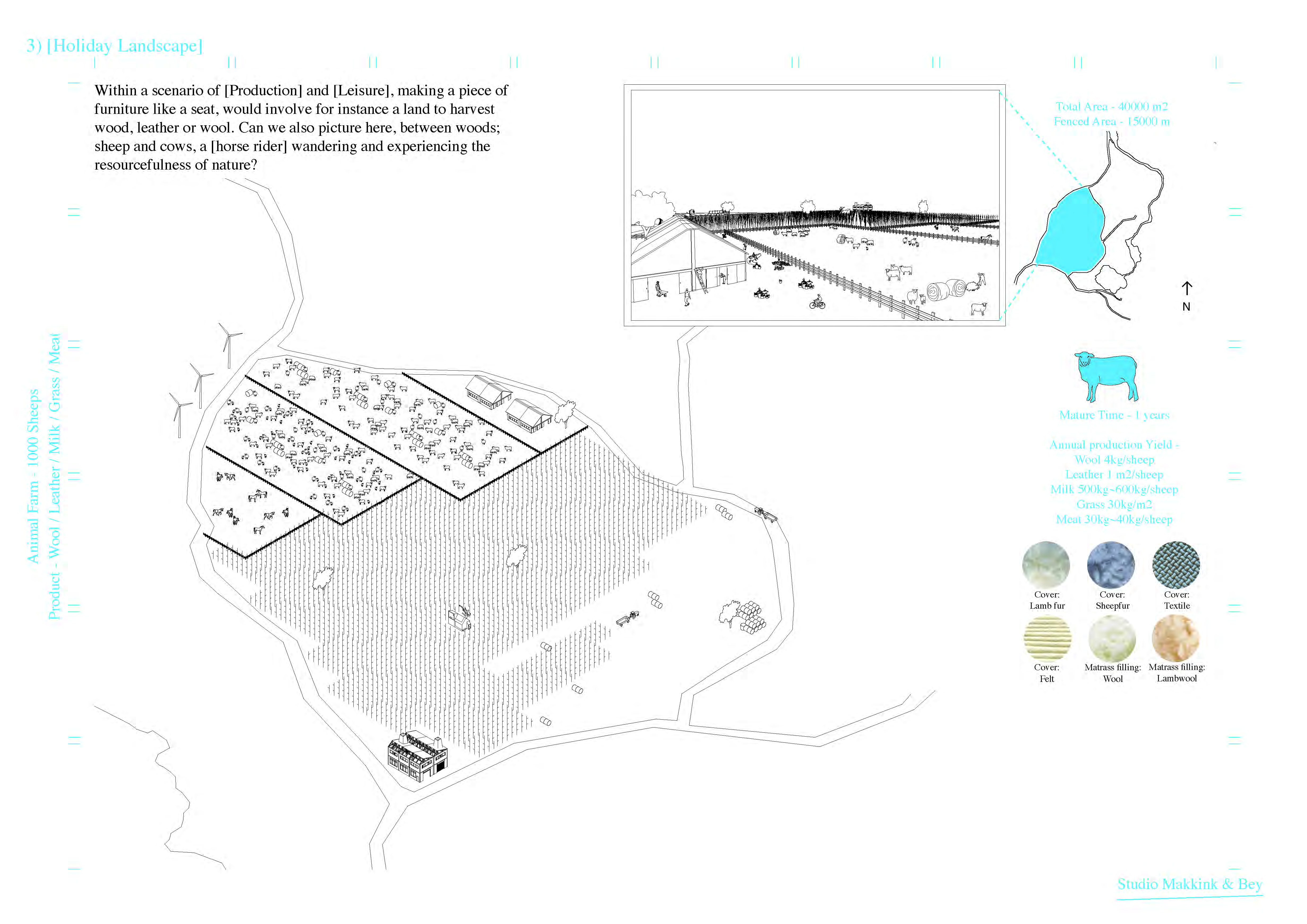

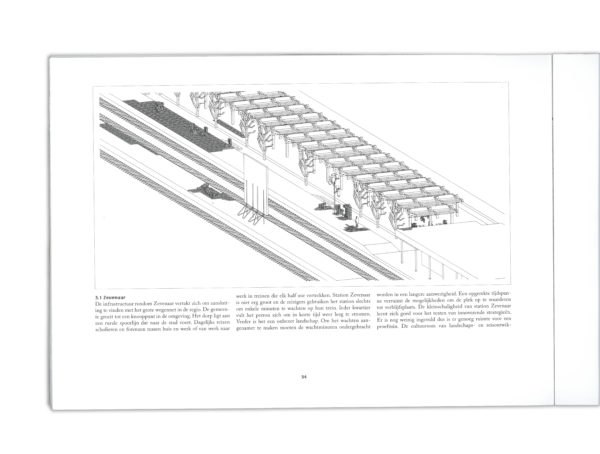

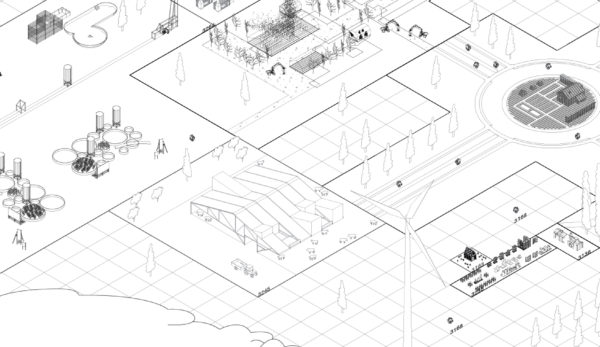

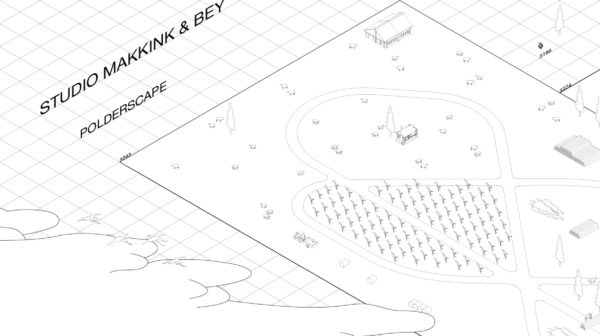

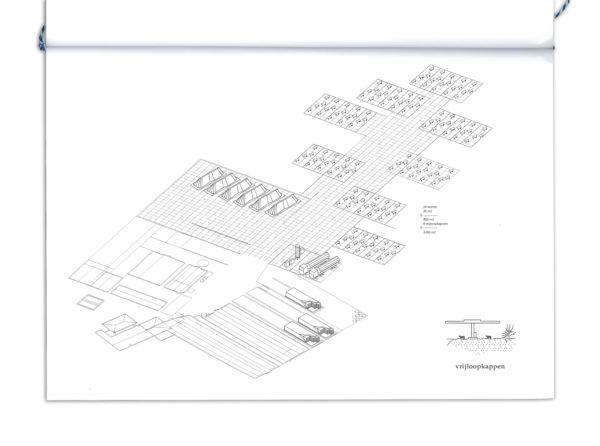

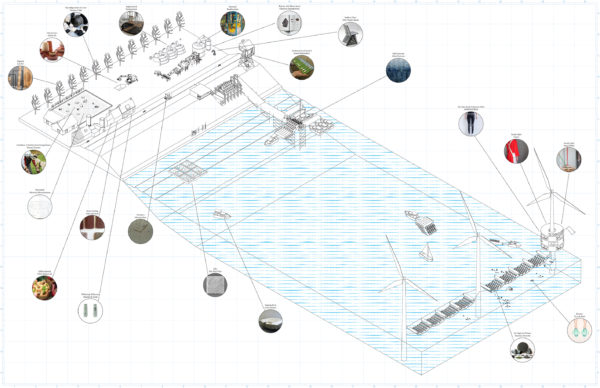

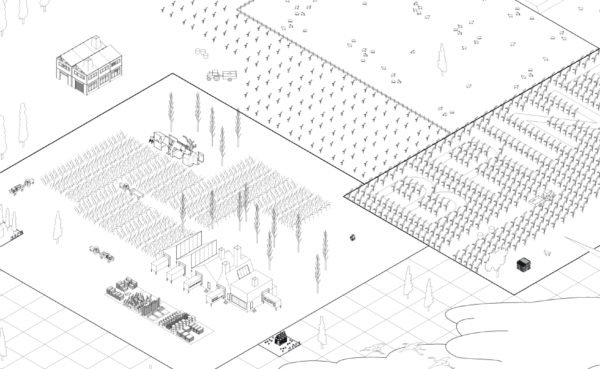

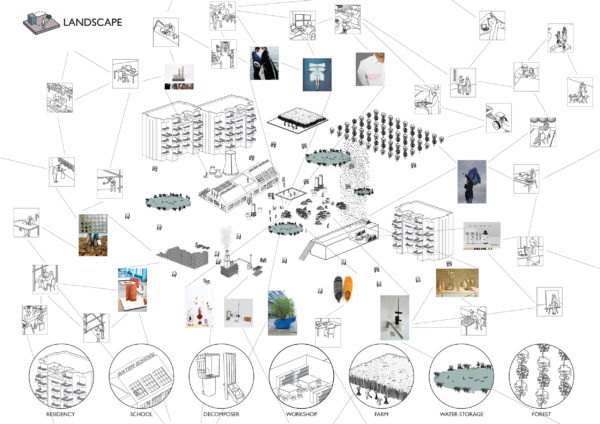

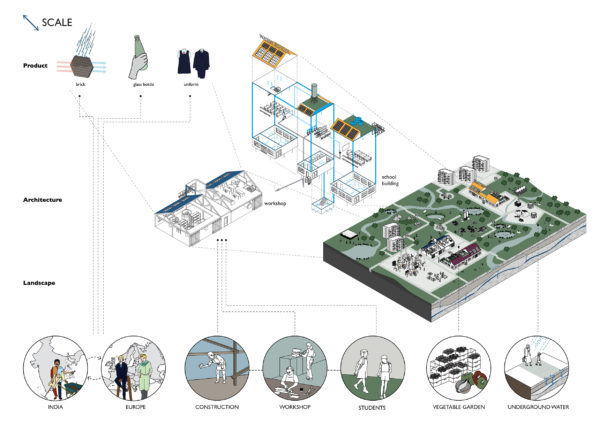

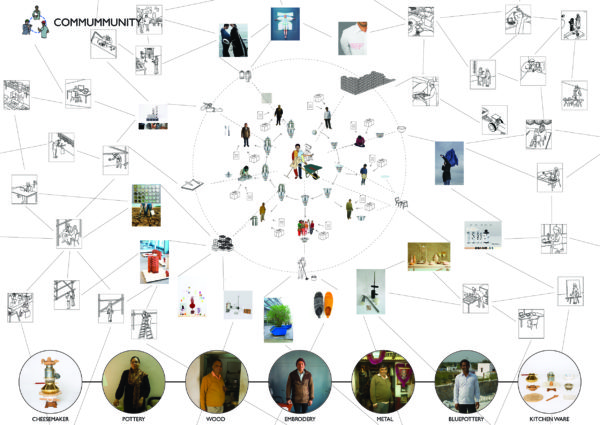

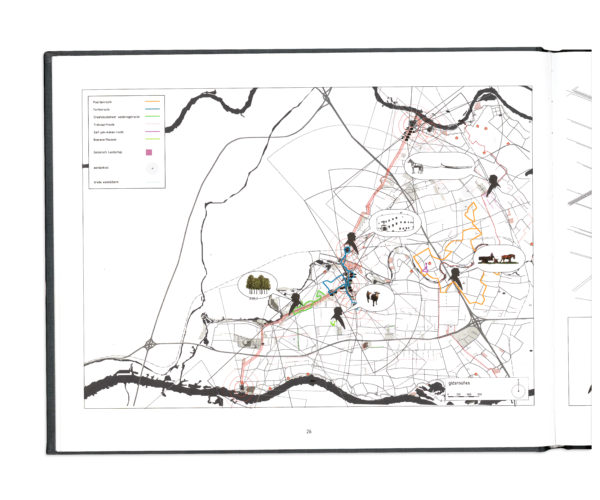

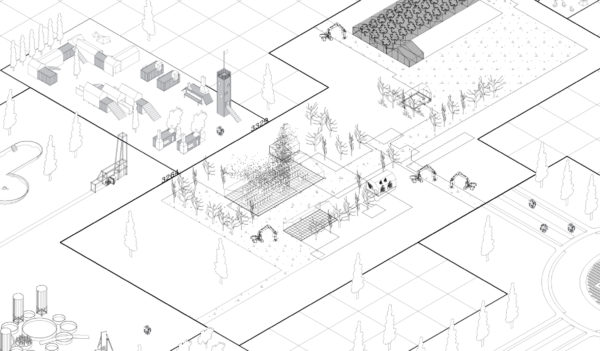

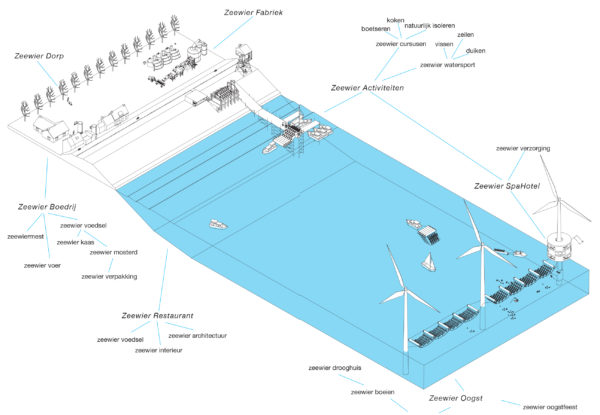

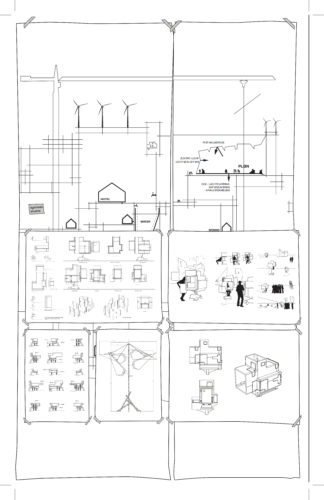

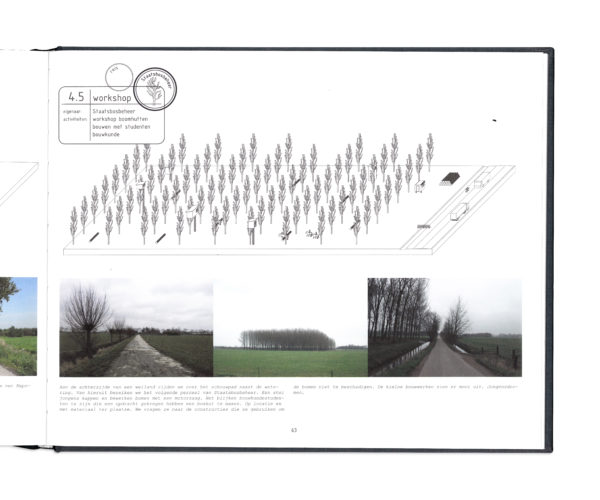

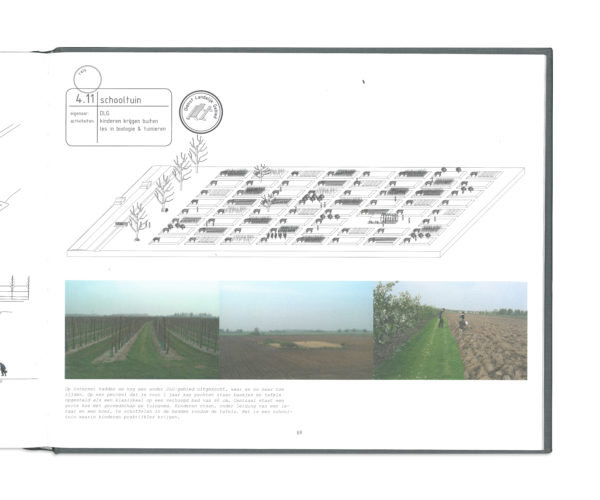

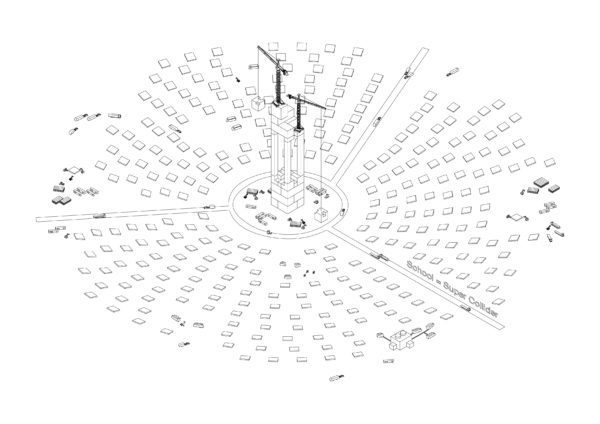

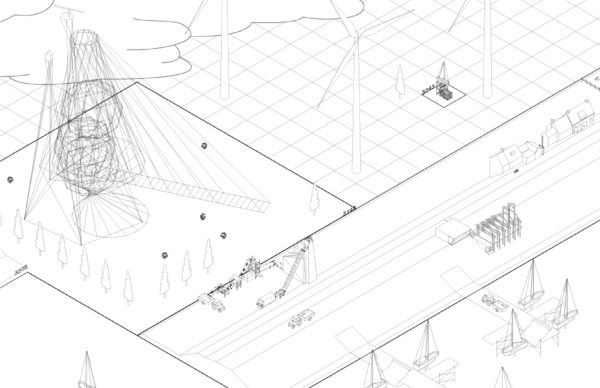

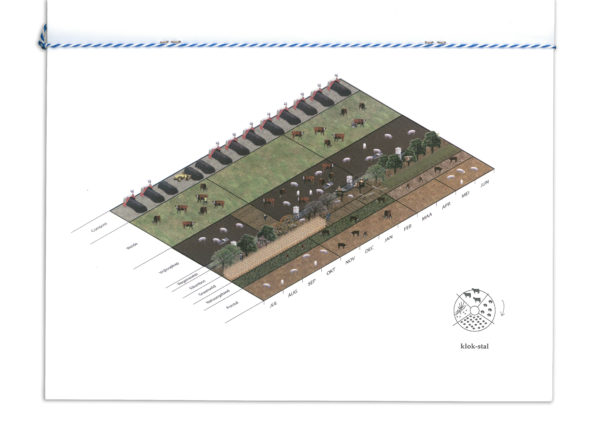

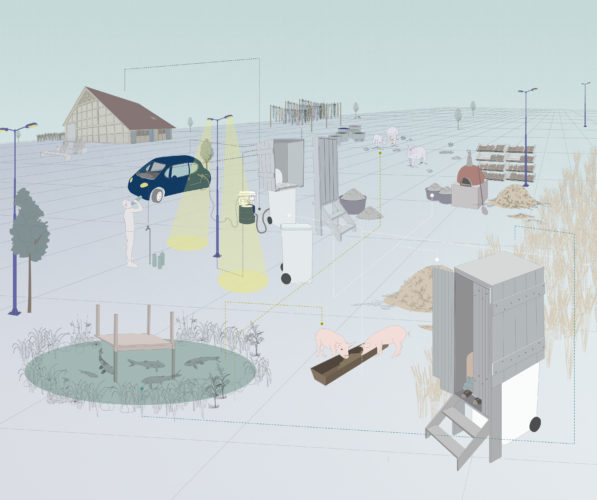

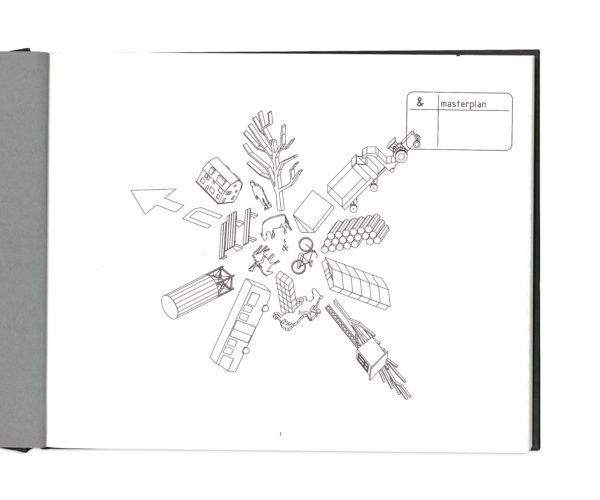

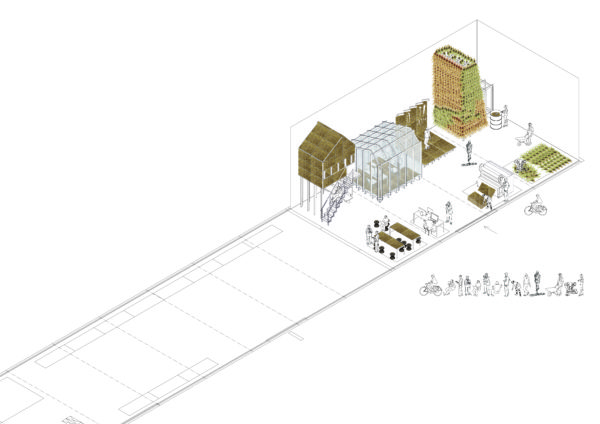

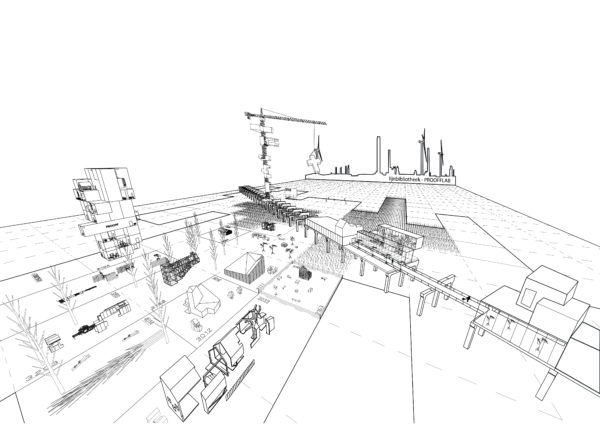

Als het landschap in dienst komt te staan van zeewier, wat voor effect heeft het dan op de traditionele professies en wat voor nieuwe beroepen zou het kunnen opleveren? Op welke manier moet het landschap opnieuw worden ingericht? Het model van De Werkplaats levert een denkkader om de mogelijkheden voor een nieuwe industrie te verkennen. Wanneer we het ontwikkelen van een zeewier industrie als startpunt nemen, waaromheen zich een community vestigt, dan zien we hoeveel ambachten – en mbo-opleidingen – betrokken zijn bij het bouwen van een dergelijke samenleving.

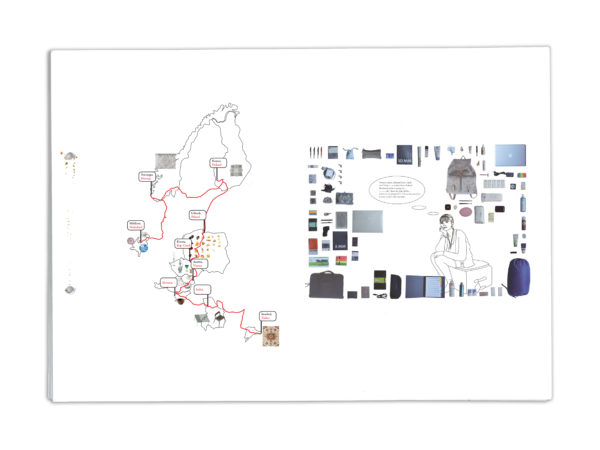

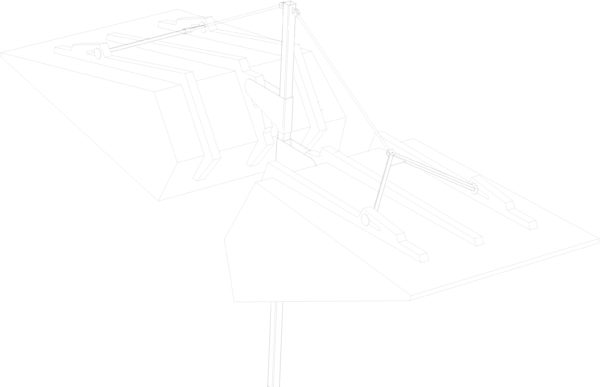

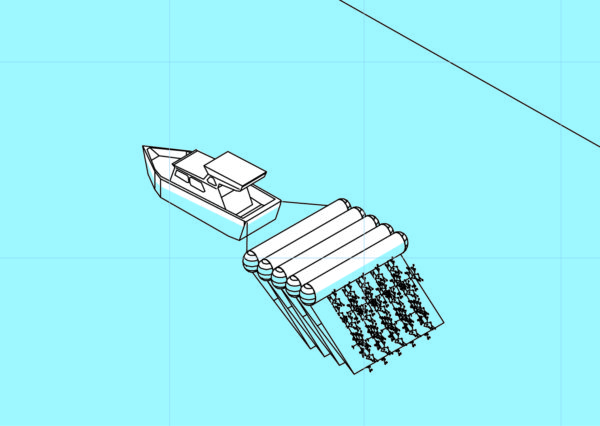

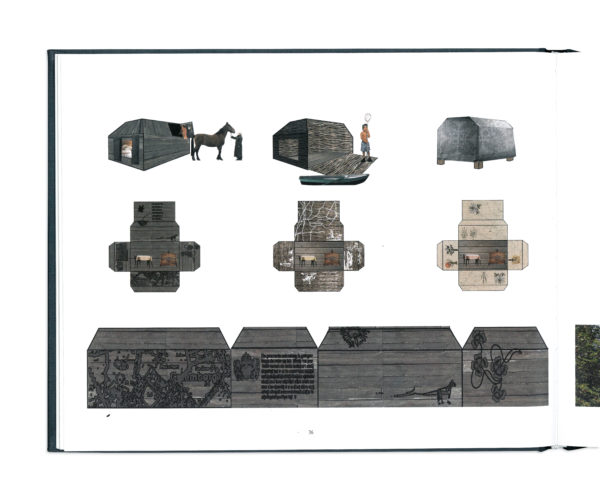

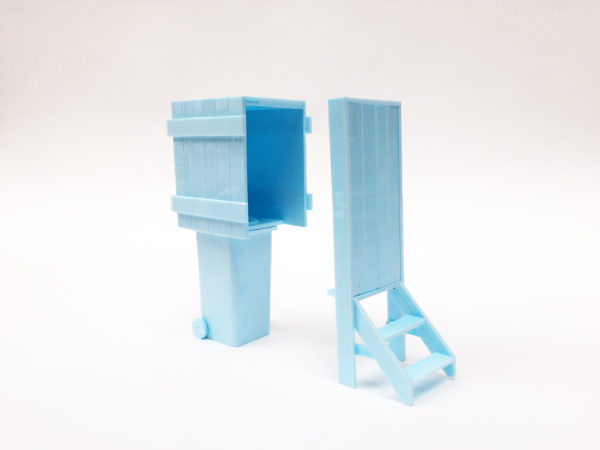

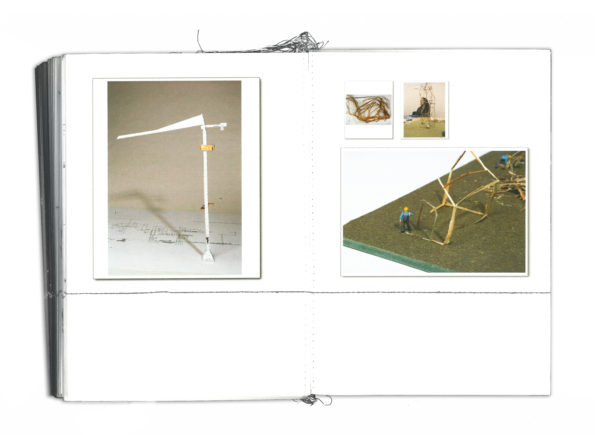

Wanneer de industrie wordt opgebouwd, is er nog geen zeewier verbouwd en geoogst, dus daarmee kan nog niet gebouwd worden. Er is een huisje nodig aan de kade; er komt een locatie van hout. Als je een kade bouwt, dan kan daar een boot aanleggen om de zeewiergebieden te bereiken. Er is een net nodig voor de oogst. Telkens worden ambachtslieden betrokken die zich vestigen en hun ambacht uitbaten. Van de netten worden kastelen geknoopt die in zee hangen, dat wordt een trekpleister voor duikers. Zo ontstaat toerisme, dus komt er een hotel, en bedden. Het hotel heeft een spa waarvoor uit het zeewier crèmes worden ontwikkeld etc.

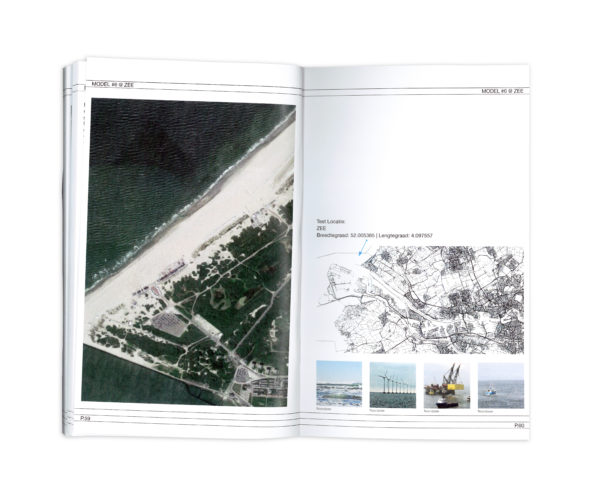

De zeewiervelden liggen vijf km uit de kust van Rotterdam. Dat valt buiten de territoriale wateren, wat zou dat voor situatie op kunnen leveren? Wat betekent het voor stedenbouw? Creëert zeewier de aanleiding om een nieuwe community te starten die buiten de bevoegdheid valt van natiestaten?

Als deze logica verder wordt uitgedacht, wordt duidelijk dat er rond zeewier een community kan groeien waarbinnen iedereen gelooft in het materiaal. Als het ware rijk je steeds naar het zeewier, maar telkens zijn er traditionele ambachten nodig om de basis te faciliteren, automotive, gezondheidszorg – beroepen die worden onderwezen op mbo-opleidingen. Iedereen die zich vestigt, neem zijn eigen achtergrond, skills en gereedschap mee, waardoor het gebied steeds aantrekkelijk wordt. Er ontstaan interdisciplinaire uitwisselingen.

–By Ellen Zoete, as published in Werkplaats Centraal (2016)